Why “The Amazing Spider-Man 2” sucks

I loved the new X-Men movie. So when the generalized chatter about the other superhero movie in theaters ran in the direction of pleasant surprise and praise, I snuck out of the house late last night to catch The Amazing Spider-Man 2 on the big screen (don’t judge — the kids were fed, warm and watched). I usually work the affronted, intellectually insulted movie patron angst through my system by spewing venom on the ride home but this time it was sitting at the foot of my bed in the morning, waiting to be picked up again.

And here I go.

Lets start with Electro’s origin story as Max Dillon, the unassuming, exploited employee of OsCorp. It is stupid to complain about done-to-death cliches in Hollywood when one has opted to watch a superhero movie. I could have blinked and embraced the irony of rooting for the cocky, self-assured “good guy” as he battles the tragically misunderstood, accidental “bad guy”. All this with just a cursory glance and indifferent shrug at the fathomless pit of despair the villain was wallowing in up till the big showdown.

Lets start with Electro’s origin story as Max Dillon, the unassuming, exploited employee of OsCorp. It is stupid to complain about done-to-death cliches in Hollywood when one has opted to watch a superhero movie. I could have blinked and embraced the irony of rooting for the cocky, self-assured “good guy” as he battles the tragically misunderstood, accidental “bad guy”. All this with just a cursory glance and indifferent shrug at the fathomless pit of despair the villain was wallowing in up till the big showdown.

But this movie not only suffers from the ethical shallowness of many a summer blockbuster. It appropriates ideals and symbols that represent the very real struggles of our time and uses them as mere props to heighten the drama of a sordid start-over or retcon (as comic book fans would call it).

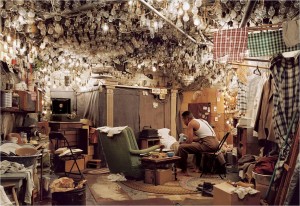

Yes, we get that Max is some poor bastard, childlike in his inability to detect deceit and childish in the the way he latches on to Spider-Man. But all those light bulbs in Max’s home, his repeated complaint of not being visible clearly indicate that the hasty construction of the villain’s tragic backstory ( which by the way, consists of some of the most annoying movie tropes — like how hilarious high-functioning autistic individuals can be, or beautiful people are good / ugly people are bad) was inspired by Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man.

The familiar knot that starts at base of the neck and sinks into the chest when confronted with the unfairness, brutality and all round contemptible display of ill manners that characterize the reality of race relations in our country started early in the movie while I sat defenseless. Because when I bought the ticket to watch this movie, I was not expecting to be reflexively blindsided by the insensitive use of an icon that represents one of the earliest, hauntingly beautiful articulations of a struggle against, among other things, being diminished, forgotten, discarded.

The familiar knot that starts at base of the neck and sinks into the chest when confronted with the unfairness, brutality and all round contemptible display of ill manners that characterize the reality of race relations in our country started early in the movie while I sat defenseless. Because when I bought the ticket to watch this movie, I was not expecting to be reflexively blindsided by the insensitive use of an icon that represents one of the earliest, hauntingly beautiful articulations of a struggle against, among other things, being diminished, forgotten, discarded.

“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.”

― Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Max Dillon, a black man, whose labor and ideas are extracted and used as if he himself were property is the shared reality of people now in the present, and of people in the past. Our ‘invisible man’ goes from sycophant to narcissist to yes, some sort of “Hollywood-movie ectoplasm”, whose death, along with its soul-stirring symbolic associations laced with the fear of black rage, is reduced to a plot device through which Gwen Stacy affirms that clever women can indeed be useful. One reductive cultural trope goes to die where another begins. Wonderful.

And now we come to the girlfriend. I must admit, I was quite prepared for it. There is after all something called “Gwen Stacy Syndrome” that lampoons the implicit sexism in comic books and how women and people of color must die tragic, untimely deaths just so the white protagonists could learn something. During the scene in which Peter Parker prances on stage and unceremoniously plants a rather coercive kiss on the valedictorian (who more importantly happens to be the hero’s girl), I found myself, of all things, missing the dweeby alter ego of Spider-Man past.

And now we come to the girlfriend. I must admit, I was quite prepared for it. There is after all something called “Gwen Stacy Syndrome” that lampoons the implicit sexism in comic books and how women and people of color must die tragic, untimely deaths just so the white protagonists could learn something. During the scene in which Peter Parker prances on stage and unceremoniously plants a rather coercive kiss on the valedictorian (who more importantly happens to be the hero’s girl), I found myself, of all things, missing the dweeby alter ego of Spider-Man past.

Barely digesting Spidey’s mood swings from lovesick puppy to smug-ass white dude, I found the sub-plot of Daddy Stacy warning Parker away from Gwen as a disconcerting representation of the chain of patriarchal concern/ control, bequeathed from one male to the next. As lame as comic books’ treatment of women can get, The Amazing Spider-Man 2 managed to see their five and raised it by ten. X-Men: Days of Future Past, on the other hand, struck out by showing how Charles Xavier needs to stop controlling women if he wants to save the world. Two steps forward, one step back. (sigh)

The movie successfully made Gwen Stacy’s death her fault, really. Why couldn’t she have just done what her boyfriend had told her to do? Why didn’t she stay glued to the taxi and why did she insist on active participation in major events? After Gwen proclaims that her actions were based on her decisions alone and not to be dictated by anyone no matter how good their intentions, I could sense something unsightly and hairy around the corner. She would die not just to give her man some badly needed depth of character, but also to pay for demanding validation based on something other than physical beauty. The girl was asserting her independence and agency. Its a surprise Spidey didn’t cry “look what you made me do” over her broken body.

My husband remarked “Gwen Stacy’s death was a kind of honor killing.” I agree. Online discussions coined the term Women in Refrigerators to describe the depowerment and elimination of female comic book characters

through gruesome injury or murder at the hands of the supervillain. What is honor killing but the depowerment and elimination of women through gruesome injury and murder.

through gruesome injury or murder at the hands of the supervillain. What is honor killing but the depowerment and elimination of women through gruesome injury and murder.

There sat a teenaged girl two seats down from me, crying her heart out through the last few minutes of the movie. I wanted to cry too. How could anyone erase or replace any of the awful subliminal messages about race and gender already at work in her mind? With a heady mixture of emotionalism and comic entertainment, all the problematic stereotypes and trite representations of women and people of color have been tweaked and reanimated for mass consumption yet again.

So yeah, the movie sucks.