“Why do Muslim women accept and believe these things anyway?”

There is this question I continually hear, when the inequalities and oppressions rampant in Muslim societies are being discussed, and it is this:

Why do Muslim women accept and believe these things anyway?

This is likely the most important question you can ask, but it can also be disappointingly wrong-headed.

I hear it from liberals, atheists, Westerners who cannot fathom someone in their right mind accepting the provisions many forms of Islam dictate for women. I hear it, too, from people from Muslim backgrounds or countries, who, despite having grown up in cultures normalizing the values they find repulsive, cannot understand their acceptance–something has been missed, for them. Last September, during the ex-Muslim strategy meeting we had in Washington DC with Dawkins and leaders of national secular coalitions, we ex-Muslims stood up and engaged with several discussion points, which included women detailing some of their thoughts and experiences under Islam. And one lady stopped in the middle of describing some of the norms in the culture she came from–interrupted herself mid sentence, as it were, and, as if the question had just occurred to her, she looked up at the panel asked “Why do Muslim women accept and believe in these things anyway?” Dawkins turned the question back onto the crowd, with a you tell me…why did you? sort of gesture.

And we stood up, in turn, we ex-Muslims in the audience, rising from our seats, speaking of the lives of the girls and women we once were, to explain the various forces that governed us, the norms that shaped the social fabric we were embedded in, details regarding ideology and cultures we came from, the influencing power of those things, the limited choices we had, the lives of our mothers, sisters, friends who still were there, who still we loved and strove to understand.

But what struck me was the nature of this question to begin with, the way it was plucked almost out of thin air, a striking inquiry that underscored and invaded a description of the lives women lead under various forms of Islam–how could they let this happen to them? and want it to?

I was struck at the air of bafflement, how mystified the lady asking the question was, how mystified Dawkins was in mirroring her question back to us, how it echoed so many discussions regarding Islam and the Middle East as ineffable, strange, other, unworldly, unholy. How unable so many people seem to be of conceiving reasons for Muslim women cleaving to Islam, how apparent it is how little they know and understand about the lived experiences of Muslim women–and more importantly, how little they care to.

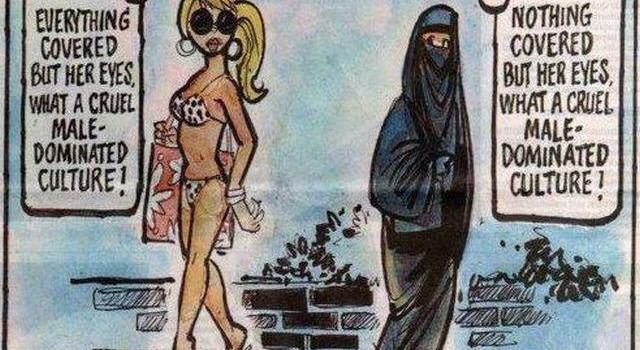

It continues to strike me how many of the people attempting to talk about Islam don’t attempt to, unless they are faced with people before them speaking about their lives, try to understand what was really going on for women like us, to consider the question from a non-othering place. That the question itself, framed with such an air of bafflement, implying weakness and stupidity on the part of its subjects, that implies also an air of smugness, superiority on the part of its questioner, preempts in its very tone the concept of there being real, compelling reasons outside the scope of the absurdity the question assumes.

Yet it should be the very first question that comes to mind. That such an important, basic question seems to be so hard for so many to conceive of is sobering in many ways. It continues to help me realize oh-so-strongly how so much of the alienation we receive as progressive Muslim and ex-Muslim women–the callous trampling upon the exploration of our stories and experiences, the continuous silencing of our voices in favor of some urgent need to generalize harshly regarding Islam or defend those who do instead of understanding how and why its problems arise–it all converges upon this same tendency to not listen to and thus by extension to not truly care about the people whose conditions and lives are really at stake here. So much of the desire to say bad things about Islam I see is not in service of helping the people who suffer under it, does not serve significant function other than to mock or insult, often in unintentionally othering and racializing manners (eg, making blanket statements that serve little function such as ‘Islam is evil’ and calling Muslim practices barbaric and savage, invoking language steeped in racial stereotype), or to defend popular figures who do the same. And it is very difficult to critique Islam in a humane way without even being concerned with understanding how and why the circumstances of our lives arise, how and why people live as they do.

It goes both ways, to be sure, with Muslim apologists elevating their desire to defend Islam as untouchable over listening to the plights and problems of Muslim women, eg the recent debacle with CAIR and the Honor Diaries, where CAIR prioritizes protesting and shutting down the screenings of a film where 9 Muslim women speak about the problem of honor violence facing women in Muslim-majority countries, choosing blanket defensiveness of Islam over listening to women and their plights, silencing the voices of those women and othering them although those women are self-identifying Muslims. But you know, while I only wish I could hope to expect better of Muslim apologists, I do expect better of skeptics, atheists, and liberals and allies of various faiths, and I do see more hope and promise in the discourse of our circles on this issue, and thus the focus of this post.

The basic question of “Why would X group of people accept or endorse dehumanizing and oppressive things” is one that, to be answered, requires alighting from a perspective of privilege, of never having been put in a position where you had to make a life out of a series of damning choices, and treating it as not an absurd question, not one with a semi-rhetorical implication of “if they had any sense they wouldn’t”. But it is not an absurd question, it is not rhetorical. It requires an answer, and not one that boils down to painting whole swaths of people as weak, brainwashed sheep. It is not one, too, that is a matter of fallaciously reducing deliberate, enforced oppression to lack of mental acuity–the stigmatization of mental illness aside, the ridiculously unscientific manners in which we speak of deliberate, inexcusable horrors as matters of individual people having delusion, idiocy, or impairment aside, such a viewpoint fundamentally lacks grounding in reality. The question is a real one, with an answer in real-world power dynamics. Answering it requires learning and becoming acquainted with the circumstances, doctrines, and systems that structure the lives of the people in question, understanding the competing considerations they must contend with, the limited choices they have–especially women. Understanding too, how other people within that society can completely bypass those choices, whose class or family or insular social web of privilege exempts them from the same problems within the same place, and how their voices are not antithesis, are not counterexample to ours, but speak to the complexity of the entire system, the insular nature of so many parts of it. Answering it, too, requires knowing that it is in fact going to be different from social context to social context, that Muslim cultures have widely varying trappings, and even common norms are perpetrated and reified within varying social structures in different ways, which is why I do not here attempt to answer the question, because it has thousands of answers, told through thousands of stories.

This is why I write posts detailing personal experiences, why my posts ring with the mantra of ‘what it is like to be a…’. what it is like. I believe this is powerful rhetoric, humanizing rhetoric, to consider just what it is like, in the most minute of everyday details, to live these things, for the reader to be forced to imagine, as it were, the experience of all of it, the complexity of the social phenomena and familial dynamics interlacing the choices we have and do not have, and how they can be remedied. This is why I’m always rejuvenated to hear feedback from people in the West, especially women, who feel that there are striking parallels between their own experiences of religious or bigoted persecution and suffering and what I’ve detailed about the lives of women like me. Because it fosters understanding. This is why, in my post regarding growing up in Hezbollah culture, I present my time growing up in Southern Lebanese guerrilla warfare culture in part by drawing parallels to so much of the religious sentiment I’ve seen normalized here in the US, that people are more likely to understand, whose perpetrators and victims are not other, who make up the social fabric of a world we must interact with, relationships we cannot drop by the wayside, because they are complex, mother-daughter, father-daughter, sister-brother, mother-son, employer-neighbor-vendor-supplier-teacher-neighborhoodwatcher and so on. And it helps, at least with some people, at least in some hearts, and that’s where I’m investing. A reader sent me this message recently:

I’ve been reading your blog, and I especially loved the entry on Hezbollah and the comparison to secluded Midwestern culture and how beliefs which seem unbelievable to outsiders are normalized there. As someone from an extremely religious community in the Southern US, I’ve seen how a lot of people believe things outsiders look at and wonder how they could possibly believe, and yet a lot of these people are basically Normal People in other ways, often even with strong ideas about conviviality and family which run weirdly parallel to their particular brand of secluded groupthink and bigotry in other ways. These complications must be understood, as you said, and that kind of nuance is something I think is missing from a lot of discussions in the West about international communities.

So much Yes.

Because I haven’t yet encountered a compelling non-experiential rhetorical method for understanding how dehumanizing and oppressive value systems are constructed and packaged, in powerful ways, within various constraints that, in order to exist and work, almost universally require their victims to view them as not-such or to attribute their source to other diversionary factors. For human beings who have experienced these things to describe their effects and influences in an informed way, for them to use that information to build arguments seems to be the most effective way to me.

Because to try to imagine what it can be like to live in places and under values you don’t know or understand, and how that might dehumanize you, and why, and in what ways, and what options and conditions and constraints feed into that, and how priorities become shifted, how reduced suffering can trump intellectual rigor can trump pride can trump honesty can trump questioning can trump skepticism: No: you cannot speculate on an experience you have not even secondhand knowledge of, and with a lack of that knowledge you cannot assume fault, weakness, or guilt of the people in question to fill the gap between your lack of understanding and reality. You cannot build a pristine dichotomy between perpetrator and victim as if they two live in vacuum instead of being products of the same system that feeds in and out, creating aggressors, normalizing aggression, when the aggressors and normalized aggression are your home and your society and your country and your relationships, your chance at bodily safety, or an education, or feeling free, unencumbered, not lost. Not when these dynamics permeate, at least a little bit, every safe place you know. You cannot assume, either, that victims do not engage with, make meaning and build anew from their oppression–you cannot paint them as drawn-down and weak, as incapable of making meaning of their lives in whatever way they best can, because they are constrained. You cannot build a binary system where the only two options are perpetrator or victim either, where there isn’t a plethora of in-between experiences, and then make claims about the what it is ludicrous and self-evident for these people to believe when your standards of the normal and the absurd are upended in the societies in question.

I read Sam Harris’ Lying, I who lived for years telling massive lies day after day for my own safety, living a double life, lying in the very gestures I made, the prayers I performed, the fasts I took, lying with my smiles, with my clothing, with my very being–how much I just wanted to be straight about everything, to shout what I really felt and thought from the rooftops. And I marveled at how such a book could so aptly exist for certain societies with enough stability and privilege for it to actually possibly be a prioritized social norm to actively consider the accumulated costs of tiny lies–mind blown. And don’t get me a wrong, how wonderful a thing it is that certain human societies have progressed so far, but how unfortunately removed from reality such a book would be in other places, some of them not too far from Sam Harris’ home, within the US. The book would be utterly irrelevant for many people like me back home, because those very caveats Harris kept making about exceptional circumstances wouldn’t be caveats anymore–not least because they are not exceptional–they would be mainstream, the norm. To think of stories, of experiences that subvert the commonly-accepted standards for normal, for absurd, that recognize the incumbency of reshuffling values and their priorities–this is one step to avoiding dehumanizing othering.

I’ve also heard several of my ex-Muslim and atheist friends express sentiments that are not so sympathetic to the rhetoric of relating experiences, who insist that critiquing Islam is most relevantly done via an exploration of its tenets, a showing through reasoning that its core theology is untenable, immoral, unjust, and/or unlikely. I think this is a position that does its fair share in perpetuating grossly simplistic forms of eg the “Cultures don’t have rights, people have rights” argument, which prima facie seems to be right on the money, because we avidly want to insist that critiquing cultural norms and the ideologies structuring them is not only fair game, but often necessary–but it can also tend to overlook that there is a point to discourse that attempts not to wholly demonize culture: cultures are composed of people, and people live under the influence of culture such that they cannot just discard its effects, reject it or subvert it to more progressive standards at once, and deconstructing culture should occur in ways that do not end up belittling and othering the very people we are critiquing culture in order to help. And I believe that critique of ideology has its own function, and I do a fair share of it myself here on this blog, but I also believe that dissecting the veracity or morality of an ideology as such does little, on its own, by way of communicating the intensity of social problems and getting people invested in doing things to fix them, and must be paired with accounts of human lives.

I must remark that I’m not speaking of anecdote, because anecdotal evidence, even if it does get people fired up and passionate due to selection bias, is quite demonstrably a shoddy argumentative tool when it claims to speak to a larger phenomena. Clearly there is a difference between mere anecdote and personal experience that reflects, is caused by, an institutionalized system whose problems are to be addressed. I am speaking here of personal stories that address and examine their own influences and causes, that accumulate into a higher social narrative, that are demonstrably supported by a scaffolding of power-privilege and social norms beneath them, that are humanizing instances of a narrative we already have good reason to believe is true, is important.

And I do believe that claims of a similar type, eg from the Muslim apologist end, treating the matters we say harm or dehumanize us as absurd or exaggerated also come from people not knowing what it is like to have those experiences, who’d rather blame the people involved in one way or another. Someone who thinks is absurd that wearing a piece of cloth on your head should lead to suffering has no real knowledge of how being reduced to the shape of your body by other people and having your family’s honor tied up into your skin can dehumanize a person. Similarly, someone who thinks it’s absurd that bullying should lead to suicide has no real knowledge of how bullying can break down a person completely. Someone who thinks it is absurd that complimenting women on the street or finding a certain race particularly attractive can hurt people has no real knowledge of how street harassment and fetishization can dehumanize a person. Someone who thinks is absurd that “mild” sexual molestation of children can lead to PTSD and long-term pain has no real knowledge of what that experience can be like. Someone who thinks it’s absurd that being sad can involuntarily incapacitate you for months has no real knowledge of the debilitating power of depression. Someone who thinks it’s absurd that cultural appropriation can be a problem has no real knowledge of how trivializing the cultural objects used to oppress people enables their further oppression. And of course, it’s not to say that these are necessary results of any of these circumstances–context, context, context–but the problem is that they are treated with the absurdity of being unlikely or impossible instead of the prevalent if not universal phenomena that they are. And from what I have seen, although scientific research and expert commentary can prove, and do prove, things of this sort, they do not have the rhetorical power that describing what it is like does, because people find it much easier to discount statistics and studies entirely, to brush them away, than they do to ignore a personal story with a clear, robust progression.

I love depression comics, like this one, for this reason, because suddenly you’re with a humanized character you can relate to, who is often funny, amiable, incisive, and ridiculously smart, following a struggle through the ‘invisible’ parts of their lives (a giant Fuck You, by the way, to people who think mental illness must undermine intelligence or rationality or moral goodness).

And it’s not just about the understanding–it’s about the understanding as a first step. Understanding what it’s like, to be and do and experience certain things helps understand those things in precisely the ways that enable productive conversations about them. And that understanding can’t come from imagination. We just don’t have that sort of predictive power, as a species yet. We don’t know enough to predict in detail how as humans we will react to things we’ve never known before. For instance I don’t believe any woman who has not worn the hijab day in and day out, from childhood, through school and work and in public and not, understanding and grappling with it in various ways, can imagine the thousands of little bits and pieces of hurt and dehumanization that can come from it. I don’t believe that people growing up in insular white communities can have any real understanding of the pervasiveness of racism in this country, unless they intimately know and love PoC who suffer from this and see the everyday struggles that face them wherever they go–likewise for people who don’t understand the struggles of being queer etc. Some people clearly think these notions absurd, others have had radically different, positive forms of a similar experience. But it’s hard to make arguments regarding these things as they affect real people without listening to these stories, learning the hows and whys of what happens to people.

So do, do ask that question of what makes people cleave to oppressive ideology, and consider it fair, just, enlightened. But ask it seriously, ask it earnestly, ask it because you care about the people it regards–and if you don’t, then go somewhere else. This is a place for those who do.

Related:

What it is like to be a Muslim woman, and why we know what freedom is

PART TWO: What it is like to be a Muslim woman

What it is like to be an ex-Muslim woman

What it is like to grow up in Hezbollah culture

HI! If you like the work I do here, consider donating a small amount to help keep this blog running, and to help me get to secular humanist conferences! I’ll be at Women in Secularism 3 this month. Come say hi!

Comment policy: I will not approve comments giving apologetic pseudo-arguments attempting to mitigate the seriousness of sexual harassment, fetishization, bullying, appropriation, mental illness etc, not least because these are examples and tangential to the post at hand, and I will no longer be drawn into debates about tangents, but also because my forum is not a place to give voice to those views, and I am not interested in educating people through their bigotries through that medium.

1 Comment

[…] This article is a very long, but worthwhile article about learning to see a religion/culture/movement from within the skin of those who inhabit such groups. […]